The Mayor of Casterbridge

In June 1949 Peter Tranchell submitted "a scenario & one scene of libretto, written in collaboration with Stephen Joseph. No music" to the Arts Council of Great Britain's opera competition for the Festival of Britain in 1951; the submission was rejected in the early stages of the competition (Foreman, 2004). But with the particular encouragement of Patrick Hadley, the work found a home with the 1951 Cambridge Festival, and was performed on 30 July 1951 by a largely amateur and student cast, at the Arts Theatre, Cambridge.

A preview. London Evening News, 17 Jan 1951: "Was his face red? – Or a Festival Opera is Born. By the time Peter Tranchell finishes writing an opera for the Festival of Britain I predict he will be permanently red in the face and chronically out of breath. For Tranchell, 28-year-old assistant lecturer in music and Cambridge University, holds his breath while composing, only drawing it in at the end of a bar. “By the end of a scene,” he told me with a broad grin, “I’m usually bright red and panting.” He gets his inspiration to write music when cycling and on the tops of buses. Gregarious by nature, he likes his home to be full of people when he is composing. His most unusual possession: a dinner jacket with a band of gold sequins worked diagonally across from shoulder to hip. A friend of Tranchell’s once suggested he should write one about “Tess of the D’Urbervilles.” Tranchell tried to borrow the book, was given “The Mayor” by mistake. Since then he has read all Hardy’s works, but still considers “The Mayor” the most suitable. This is Tranchell’s first large-scale work. But he has written incidental music for amateur productions of anything from Priestley’s “Johnson Over Jordan” to “Macbeth.” This was partly at Eastbourne College where he taught music for a year and partly as an undergraduate at Cambridge."

A review. "Tranchell has seized the mood of Hardy's novel with a precision uncanny in a composer whose idiom seems naturally so sophisticated.... He has devised ensembles, duets, and other set pieces with a strongly effective, and fundamentally romantic feeling for mood and placing." and "If not a total success, then, The Mayor of Casterbridge offered promise and much compelling interest for anyone interested in the development of an English operatic tradition." (The Times, 31 July 1951, 8 (Times Digital Archive). And Eric Blom (editor of Music & Letters), in reviewing the opera in The Observer, London, Sunday, August 5, 1951, remarked: "Mr Tranchell has decidely leapt to fame at a single bound. His second act is a near-masterpiece." and overall called it "an English stage work of exceptional quality."

Tranchell described the "tribulations of a composer getting his first opera performed" in A Cambridge Opera in Cambridge Today Michaelmas Term 1951.

The opera was performed again in 1959, by the Cambridge University Opera Group, produced by David Byram-Wigfield and conducted by Guy Woolfenden. According to the biography of David Byram-Wigfield (Tim Byram-Wigfield, 2000, Emmanuel College Magazine 2019-10), the production was featured on BBC TV’s In Town Tonight, as a result of which David secured a place on the production staff at Glyndebourne opera.

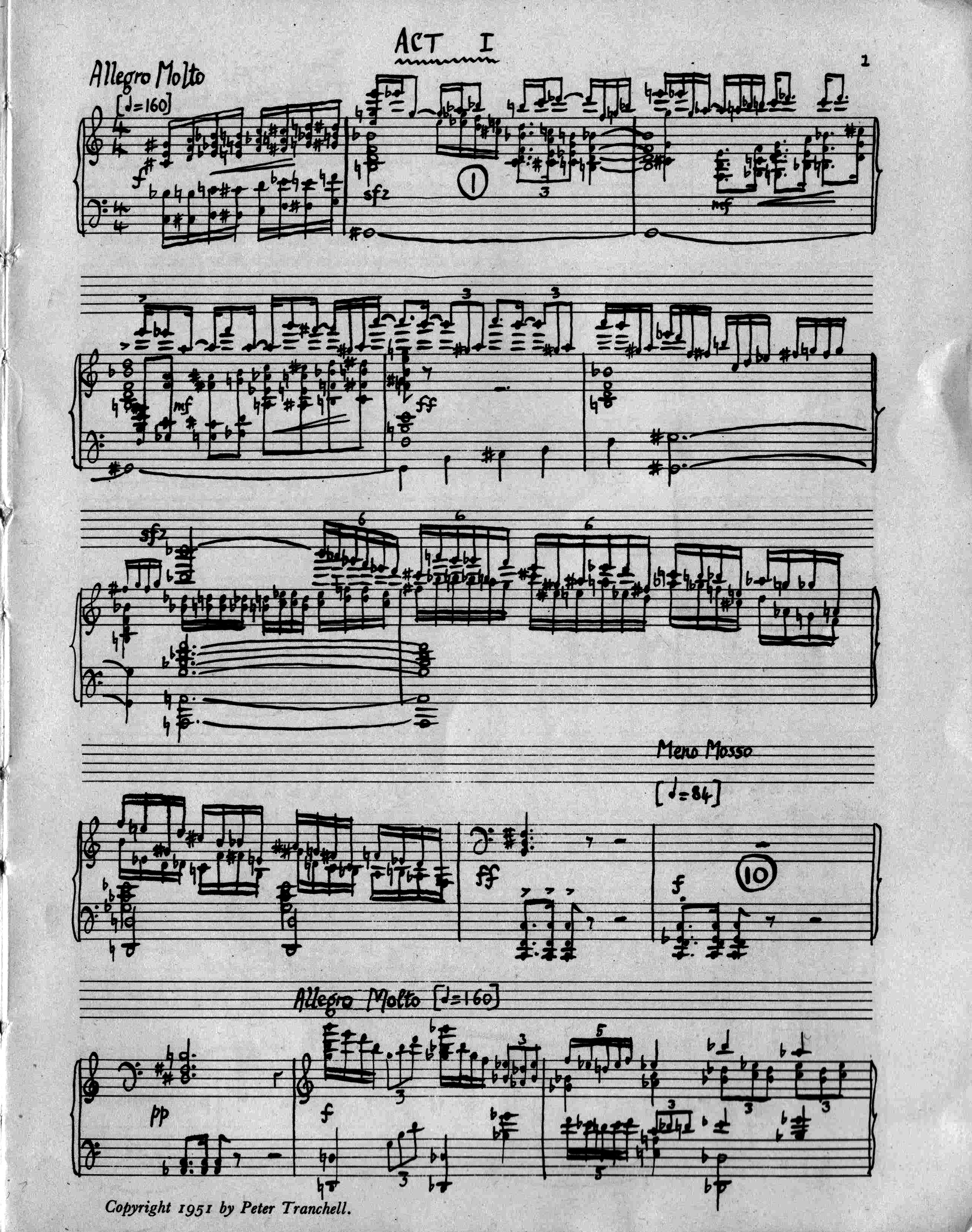

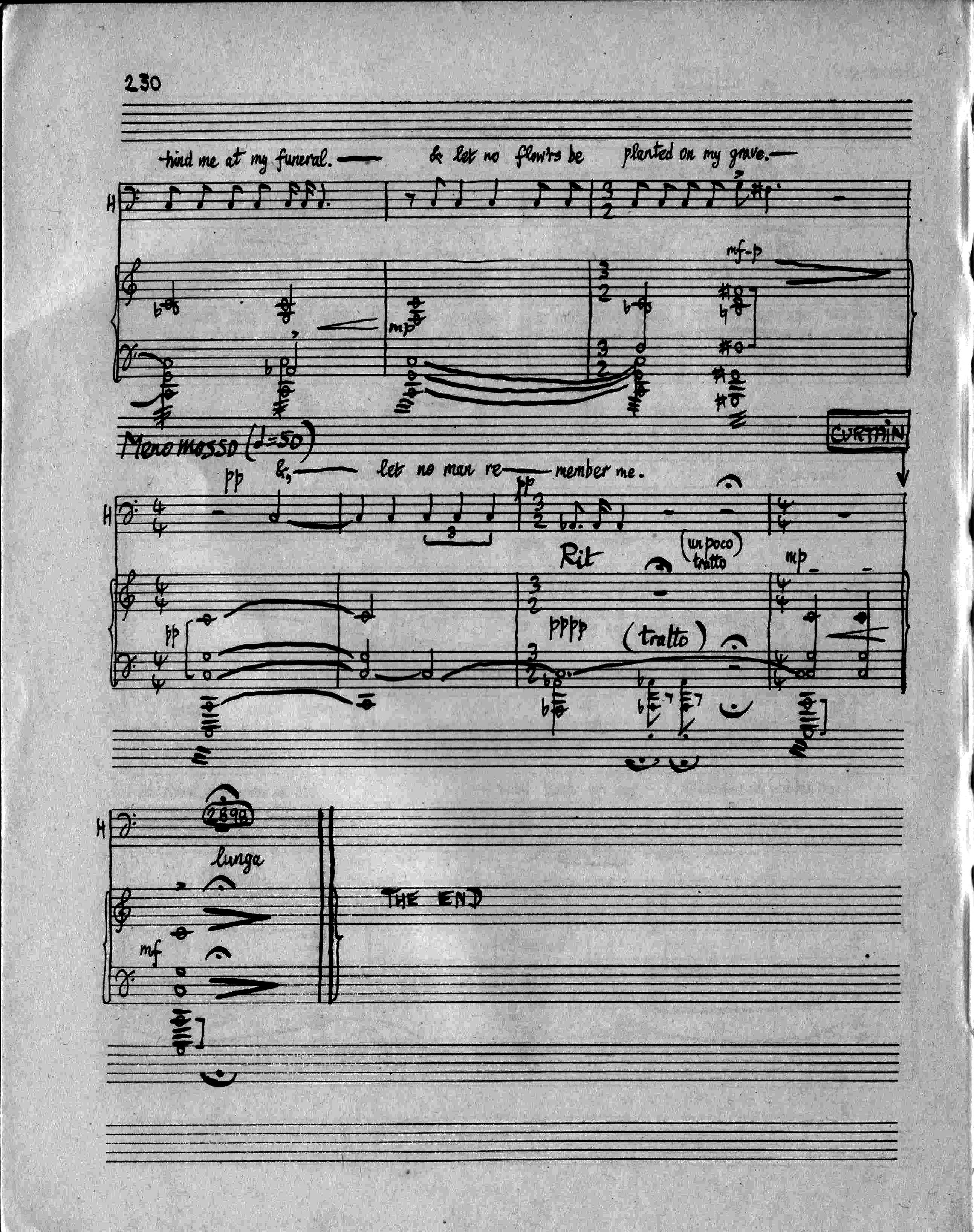

Here are some scans of the original vocal score from 1951, the music written in Tranchell's own hand.

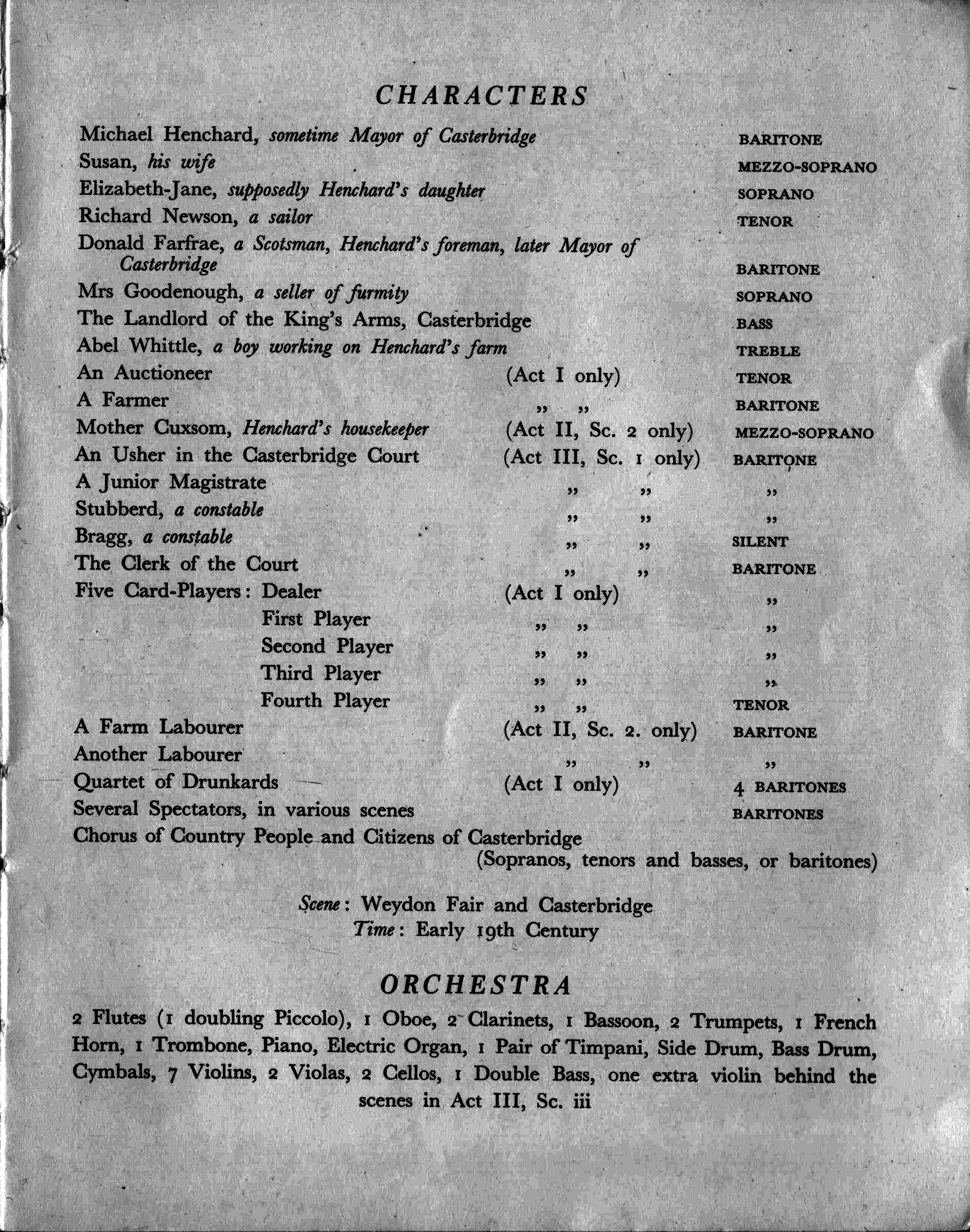

List of characters

The opening bars, subsequently revised for the 1959 staging.

The end - bar 2898!

Recording of Closing Scene: The Mayor of Casterbridge from the Commemoration CD.

Use the player below or download the MP3:

Henchard: Alan Opie (baritone)

Whittle: Roderic Keating (tenor)

Elizabeth-Jane: Alex Kidgell (soprano)

James Gibson and Thomas Hewitt Jones (pianos)

Reviews & Letters

A letter from Ralph Vaughan Williams

A letter from Ralph Vaughan Williams

The Times 31 July 1951

Tranchell has seized the mood of Hardy’s novel with a precision uncanny in a composer whose idiom seems naturally so sophisticated. The normal language might be taken for folk song, modality and diatonicism, but this composer’s idiomatic basis is a chromatic diatonicism, and the accents with which he clothes the melodic bones of his melody give the piece a freshness that belongs to the English countryside. He has devised ensembles, duets, and other set pieces with a strongly effective, and fundamentally romantic, feeling for mood and placing. The weakness of this opera is the flat quality of the melody and harmony, when folk atmosphere is not being evoked, and when climaxes are not in question. There are still the broad lines and many individual passages which demand musical attention and produce a marked impact… If not a total success, then, The Mayor of Casterbridge offered promise and much of compelling interest for anyone concerned with the development of an English operatic tradition.

[almost certainly by William Mann]

The Observer 5 August 1951: New Composer, by Eric Blom

Cambridge offered us a new opera by a hitherto quite unknown composer, Peter Tranchell, and one that made an immediate and forceful impression. [...orchestra would have done better under a more experienced conductor than the composer...]

As a creative artist Mr Tranchell has decidedly leapt to fame at a single bound and almost recklessly high. His second act is a near-masterpiece, with music apt to situation, full of atmosphere, making shapely composition without distorting the action and, above all, full of really personal and striking invention, often daringly harsh, but never sacrificing musical to ostentatious effect. The rest, with very difficult crowd scenes, is not quite on the same level, but those scenes are on the whole very skilfully managed.

“The Mayor of Casterbridge” may not become a Hardy annual of English opera, mainly because there are no such things, but it is an English stage work of exceptional quality.

News Chronicle 6 August 1951

The new opera “The Mayor of Casterbridge,” by the young, hitherto unknown composer Peter Tranchell, is one of the most distinguished events of the Festival of Britain celebrations in Cambridge. It is undoubtedly one of the most exciting musical events of the year. In a most auspicious manner it brings to the fore a fresh renown. I attach importance to this very able, rather uneven, very poetic and vital first operas not only as regards the future of the composer, but for the whole future of British opera.

Hardy’s tragedy has been reduced to fit into three acts; which means that only the bare bones remain. These Mr. Tranchell has clothed with effective music, true operatic music, romantic and rich. It is contemporary music but not outlandishly modern. The third act needs revising. The second act is quite splendid. The first act with its crowd scene needs a bigger stage than the Arts Theatre and should one day have it. The cast last night and the orchestra played to the best amateur traditions. I have no intention to discredit them when I say that this opera ought now to be given according to the finest professional standards.

Scott Goddard.

From "Alan BUSH, Arthur BENJAMIN, Berthold GOLDSCHMIDT, Karl RANKL, Lennox BERKELEY & THE ARTS COUNCIL’s 1951 OPERA COMPETITION by Lewis Foreman"

Read more: http://www.musicweb-international.com/classrev/2004/feb04/Foreman_opera.htm#ixzz5I9TDuTXW

Unfortunately there was no opera from the competition that might have crowned this activity, though Peter Tranchell’s competing opera The Mayor of Casterbridge, rejected by the competition at an earlier stage, was produced at Cambridge in 1951, and might well have been capable of fulfilling the expectations of the organisers. Unfortunately it was side-lined by the simultaneous production of Billy Budd at Covent Garden.

The Manchester Guardian 6 August 1951 (reprinted in the weekly edition 9 August)

In the evening at the Arts Theatre was given the last of the eight festival performances of the new opera by Peter Tranchell, “The Mayor of Casterbridge,” to a libretto after Hardy. In this it would seem as if the work of Britten in the field not of chamber opera but of grand opera (i.e. “Peter Grimes”) were bearing fruit. There is a distinct similarity in the subject for in both the tragic hero is the villain, who wins the compassion of the audience when too severe a retribution and the pitiless persecution of the narrow community in which he lives fall upon him. The structure of the opera is also slightly similar in that it has a short first act in one scene which is dramatically equivalent to the prologue to “Grimes”. Mr Tranchell gives evidence of an outstanding talent in conveying the tragedy of the story not too skilfully but at his best very movingly, in spite of the disadvantages of a small stage and a largely amateur (though rarely amateurish) cast and orchestra and a libretto that has a number of dramatic awkwardnesses and irrelevancies as well as over-many prosy lines.

This is where the composer, too, most often falls. He cannot pedal along between climaxes or write interesting music for moments where the dramatic tension needs to be relaxed. This may be partly the fault of his harmonic idiom, which is broadly eclectic and full of strong, almost aggressive vitality, but tends to lack emotional variety. Here, however, he is in good company, for some of the most important modern music, notably that of the so-called “atonalists,” shares the same characteristic. Some of Mr Tranchell’s own melodic and harmonic resources are of the same order but he shows considerable originality in containing them within a tonal framework. Where the music fails one feels that the composer has been the victim of his own libretto, for he rises to its best moments so well that if the sections which are aside to the main drama but are legitimate in opera for the sake of music had been more skilfully made he would probably have found the right music for them. At all events such miscalculations as the opera contains are all of a kind that can be avoided with experience. And it already has those essential positive qualities that experience cannot teach.

C.M.

"A.J.", The Musical Times, Vol. 92, No. 1303 (Sep., 1951), p. 421. 'The Mayor of Casterbridge'

The Cambridge Festival (28 July to 18 August) presented on 30 July at the Arts Theatre the first performance or Peter Tranchell's opera 'The Mayor or Casterbridge'. The composer, who is twenty-nine, is an assistant lecturer in music at Cambridge University. Peter Bentley, also of the University, was the producer. The men collaborated on the libretto, which is a compressed and crude version of Thomas Hardy's novel. Compressed, no doubt, it had to be. But the total omission of Lucetta made the romance of Farfrae and Elizabeth-Jane flat and conventional. Their first encounter, turning into a flirtation, was ludicrous and indeed embarrassing; though a more experienced producer would have made it less so. Such a producer would, indeed, have smoothed out several other awkward moments, and would have avoided the over-crowding of the stage during the opening scene when Henchard gets drunk and sells his wife. The musical texture of Tranchell's score is thick; its basic idea often seems to be the addition of one or two wrong notes to the right chord. But it is skilfully orchestrated, and sounds both less jagged and less monotonous harmonically than it looks in vocal score. The music cannot however be said to do more than keep the listener mildly interested while he waits in vain for a moment of compulsion or illumination. Yet in his forceful setting of words, and in his appreciation of the need for a well-balanced layout of solos, ensembles, and choruses, Tranchell reveals a certain sense of theatre which may bear fruit in future. Robert Rowell, one of the few professionals in the cast, sang creditably as Henchard; so did José Stubbings, as his wife. Farfrae (Antony Vercoe) was likeable, but, without a Scots accent, unbelievable. The orchestra, which included piano and electric organ, was mainly composed of students from the Royal College of Music and was conducted by the composer.